LONDON (CNNMoney) Europe, seeking to reduce its dependence on Russian natural gas, is encouraging political leaders to step up efforts to tap the region's shale gas deposits.

LONDON (CNNMoney) Europe, seeking to reduce its dependence on Russian natural gas, is encouraging political leaders to step up efforts to tap the region's shale gas deposits. Jose Manuel Barroso, president of the European Commission, the EU's executive body, said growing tension with Russia over its actions in Ukraine serve as a "very strong wake-up call for Europe" about energy issues.

"Europe is working very decisively to reduce its energy dependency," he said last week at an EU-U.S. summit in Brussels.

Europe can pursue many long-term options such as ramping up renewable energy production and importing liquefied natural gas, both expensive propositions. But shale gas continues to be front of mind among energy ministers and policymakers.

Accessing nearby shale gas resources would be cheaper than other options and could create up to one million jobs in the coming years, according to research commissioned by the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers.

"The outlook [for shale] is undoubtedly brighter now than it was a year ago," said energy analysts at Eurasia Group.

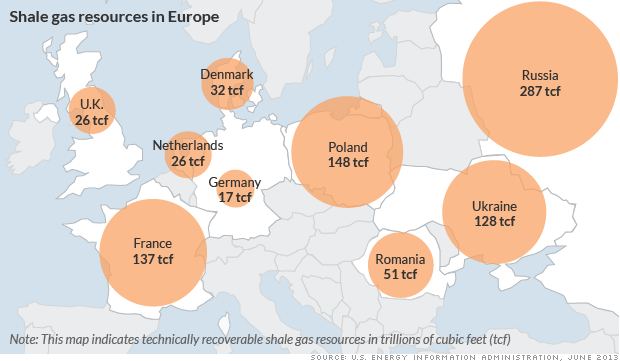

According to figures from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, European countries are sitting on roughly 470 trillion cubic feet of recoverable shale gas resources -- a huge amount considering gas demand in Europe is roughly 18 trillion cubic feet per year.

But it's not going to be an easy process: Europe's shale gas production is essentially zero right now, and it will take a coordinated effort to get moving.

Pavel Molchanov, an energy analyst at Raymond James, says the whole process will take years.

"Over the next five years, [European] countries will have to identify where their resources are and build out the infrastructure for this industry to develop -- that can include developing pipelines and training workers," he said. "This also means getting the required rigs to drill for shale gas, which are in the U.S. and Canada, but don't really exist in Europe."

On top of that, a web of regulations is slowing progress, and environmental concerns about the process of extracting shale gas have led some European countries to ban the practice altogether.

The controversial extraction process -- called hydraulic fracturing, or fracking -- involves injecting water, sand and chemicals deep into the ground at high pres! sure to crack shale rock, allowing oil and gas to flow.

This practice has spurred America's energy boom, but opponents argue fracking can contaminate local water, create earth tremors and wreak havoc on the environment.

Despite the obstacles, the United Kingdom and Poland are making the biggest strides in pursuit of shale gas production.

"Poland is the furthest along. It's conceivable that in the next five years we could see meaningful production," said Will Pearson, director of global energy and natural resources at Eurasia Group.

Lithuania, Romania and Ukraine are also keen to pursue shale, he said.

Meanwhile, other countries are less enthusiastic. Germany, Denmark, Ireland and the Netherlands have informal fracking bans, requiring so much onerous documentation and pre-drilling research that energy companies are hesitant. Bulgaria and France have outright fracking bans.

"It will take awhile before France and Germany change their policies toward shale," said Pearson, but "hostility toward the sector is going to dissipate" as Europe tries to decrease its dependence on Russian energy.

There's debate over when European shale gas production might start making a dent in the gas market, but experts aren't expecting anything significant until 2020 at the earliest.

"Shale gas production in Europe is effectively zero. Twelve months from now it will still be zero. Five years from now, it will be more than zero," said Raymond James analyst Molchanov.

Fracking fight hits England

Fracking fight hits England Over the medium term, Europe is working on building more interconnected links and storage facilities to give nations more flexibility with their natural gas supplies.

The process "is not very glamorous," says Pearson, but it wi! ll help E! urope reach its goal of greater energy independence. ![]()

No comments:

Post a Comment